Making the move from Scala to Go, and why we’re not going back

NOTE: my original blogpost was published in the Movio blog. I’ve had to steal it because it went offline for a while, the link sometimes 404s, and they’ve broken some links. I don’t want it to be lost. The following content is unchanged from the original.

UPDATE: This blogpost has received a lot of attention since it’s been published, including on Hacker News, Golang Weekly and Scala Times; thank you! Unfortunately, some readers have considered it strictly an attack on the Scala community and/or a biased episode of language war. This was not the Red Squad’s intention. As explained within the text, Movio uses Scala; some squads use Scala as their main language. We have hosted Scala Downunder two years ago. The Scala community has taught us a lot during the past 4 years. Scala and Go coexist at Movio.

Here’s the story of why we chose to migrate from Scala to Go, and gradually rewrote part of our Scala codebase to Go. As a whole, Movio hosts a much broader and diverse set of opinions, so the “we” in this post accounts for Movio Cinema’s Red Squad only. Scala remains the primary language for some Squads at Movio.

Why we loved Scala in the first place

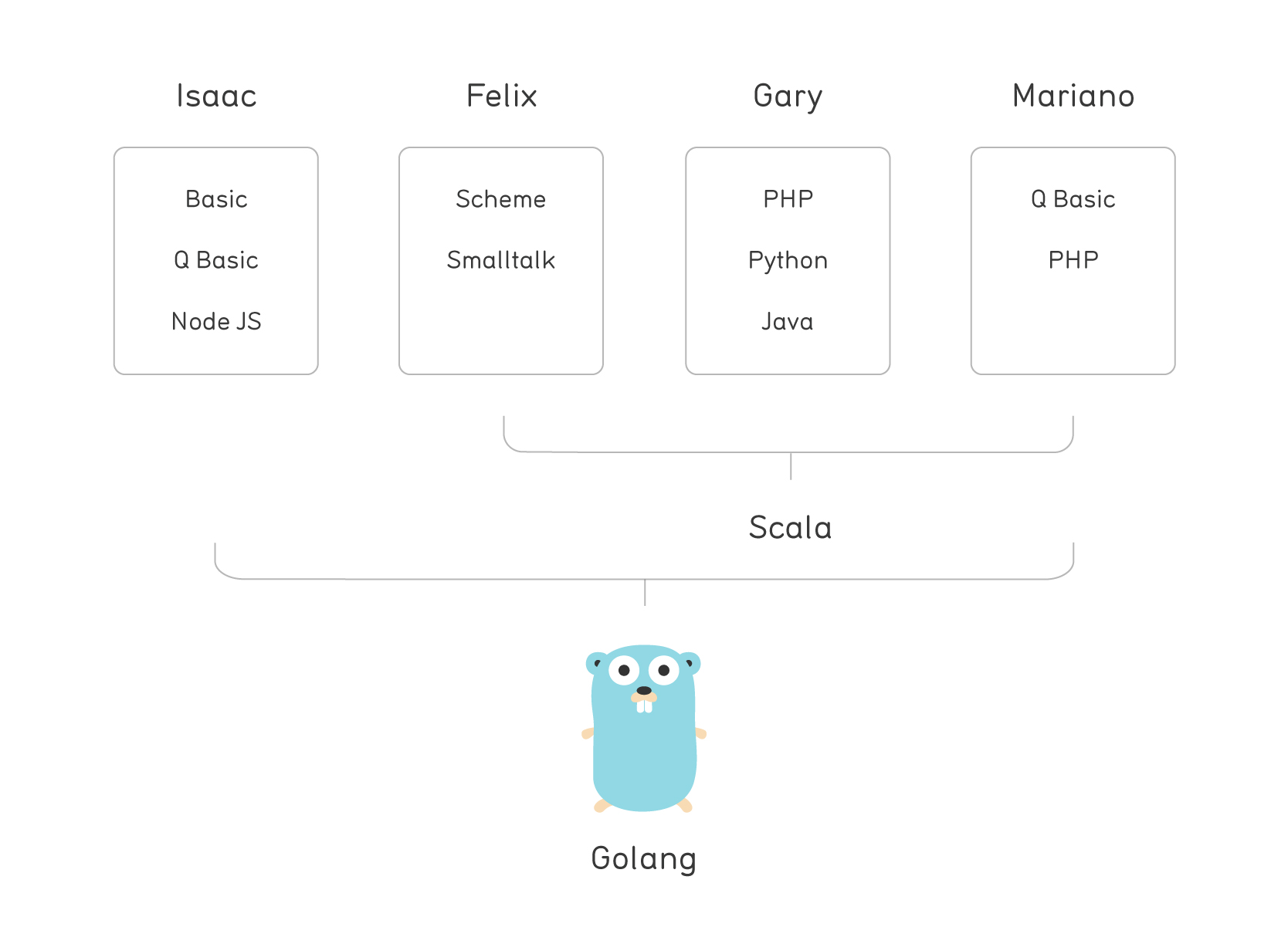

What made Scala so attractive? This can easily be explained if you consider our backgrounds. Here’s the succession of favorite languages over time for some of us:

As you can see, we largely came from the stateful procedural world.

With Scala coming onto the scene, functional programming gained hype and it really clicked with us. Pure functions made deterministic tests easy, and then TDD gained popularity and also spoke to our issues with software quality.

I think the first time I appreciated the positive aspects of having a strong type system was with Scala. Personally, coming from a myriad of PHP silent errors and whimsical behavior, it felt quite empowering to have the confidence that, supported by type-checking and a few well-thought-out tests, my code was doing what it was meant to. On top of that, it would keep doing what it was meant to do after refactoring, otherwise breaking the type-checking or the tests. Yes, Java gave you that as well but without the beauty of FP, and with all the baggage of the EE.

There are other elusive qualities that make Scala extremely sexy for nerds. It allows you to create your own operators or override existing ones, essentially being unary and binary functions with non-alphanumeric identifiers. You can also extend the compiler via macros (user-defined functions that are called by the compiler), and enrich a third-party library via implicit classes, also known as the “pimp my library” pattern.

But Scala wasn’t without its problems.

Slow compilation

The slowness of the Scala compiler, an issue acknowledged and thoroughly described by Martin Odersky, was a source of constant frustration. Coupled with a big monolith and a complex dependency tree with a complicated resolving mechanism - and after years of great engineers babysitting it - adding a property on a model class in one of our core modules would still mean a coffee break, or a sword fight. Most importantly, it became rare to have acceptable coding feedback loop times (i.e. delays in between code-test-refactor iterations).

Slow deployments

Slow compile times and a big monolith meant really slow CI and, in turn, lengthy deploys. Luckily, the smart engineers on Movio Cinema’s Blue Squad were able to parallelize module tests on different nodes, bringing the overall CI times from more than an hour to as little as 20 minutes. This was a great success, but still an issue for agile deployments.

Tooling

IDE support was poor. Ensime’s troubles with multiple Scala version projects (different versions on different modules) made it impractical to support optimize imports, non-grep-based jump to definition, and the like. This meant that all open-source and community-driven IDEs (e.g. vim, Emacs, atom) would have less-than-ideal feature sets. The language seems too complex to make tooling for!

Even the more ambitious attempts at Scala integration struggled on multiple project builds, most notably Jetbrains’ Intellij Scala Plugin, with jump-to-definition taking us to outdated JARs rather than the modified files. We’ve seen broken highlighting on code using advanced language features, too.

On the lighter side of things, we were able to identify exactly whether a programmer was using IDEA or sbt based purely on the loudness of their laptop fans. On a MacBook Pro, this is a real problem for anyone hoping to embark on an extended programming session away from a power outlet.

Developments in the global Scala community (and non-Scala)

Criticism for object-oriented programming had been lingering in the office for some time, but it hadn’t reached mainstream status until someone shared this blog post by Lawrence Krubner. Since then, it has become easier to float the idea of alternative non-OOP languages. For example, at one stage there were several of us learning Haskell, among other experiments.

Though old news, the famous 2011 “Yammer moving away from Scala” email from Coda Hale to the Scala team started to make a lot of sense once our mindset shifted. Consider this quote:

“A lot of this [complexity] has been waved away as something only library authors really need to know about, but when an library’s API bubbles all of this up to the top (and since most of these features resolve specifics at the call site, they do), engineers need to have an accurate mental model of how these libraries work or they shift into cargo-culting snippets of code as magic talismans of functionality.”

Since then, bigger players have followed, Twitter and LinkedIn being notable examples.

The following is a quote from Raffi Krikorian on Twitter:

“What I would have done differently four years ago is use Java and not used Scala as part of this rewrite. […] it would take an engineer two months before they’re fully productive and writing Scala code.”

Paul Phillips’ departure from Scala’s core team, and his long talk discussing it, painted a disturbing picture of the state of the language - one of stark contrast to the image we had.

For further disturbing literature, you can find the whole vanguard of the Scala community in this JSON AST debate. Reading this as it developed left some of us feeling like this:

The need for an alternative

Until ‘Go’ came into the spotlight, though, there seemed to be no real alternative to Scala for us; there was simply no plausible option raising the bar. Consider this quote from the popular Coursera blog post ‘Why we love Scala at Coursera’:

“I personally found compilation and reload times pretty acceptable (not as tight as PHP’s edit-test loop, but acceptable given the type-checking and other niceties we get with Scala).”

And this other one from the same blog post:

“Yes, scalac is slow. On the other hand, dynamic languages require you to incessantly re-run or test your code until you work out all the type errors, syntax errors and null dereferencing. I’d rather have a sip of coffee while scalac does all this work for me.”

Why ‘Go’ made sense

It’s simple to learn

It took some of us six months including some after hours MOOCs, to be able to get relatively comfortable with Scala. In contrast, we picked up ‘Go’ in two weeks. In fact, the first time I got to code some Go was at a Code Retreat about 10 months ago. I was able to code a very basic Mario-like platform game!

We’ve also feared that a lower-level language would force us to deal with an unnecessary layer of complexity that was hidden by high-level abstractions in Scala e.g. Futures hiding threads. Interestingly, what we’ve had to review were things like signals, syscalls and mutexes, which is actually not such a bad thing for so-called full-stack developers!

For the first time ever, we actually read the language spec when we’re unsure of how something works. That’s how simple it is; the spec is readable! For my average-sized brain, this actually means a lot. Part of my frustration with Scala (and Java) was the feeling that I was never able to get the full context on a given problem domain, due to its complexity. An approachable and complete guide to the language strengthens my confidence in making assumptions while following a piece of code, and in justifying my decision-making rationale.

Simpler code is more readable code

No map, no flatMap, no fold, no generics, no inheritance… Do we miss them? Perhaps we did, for about two weeks.

It’s hard to explain why it’s preferable to obtain expressiveness without actually ‘Go’ing through the experience yourself - pun intended. However, Russ Cox, Golang’s Tech Lead, does a good job of it in the “Go Balance” section of his 2015 keynote at GopherCon.

As it turned out, more flexibility led to devs writing code that others actually struggled to understand. It would be tough to decide if one should feel ashamed for not being smart enough to grasp the logic, or annoyed at the unnecessary complexity. On the flip side, on a few occasions one would feel “special” for understanding and applying concepts that would be hard for others. Having this smartness disparity between devs is really bad for team dynamics, and complexity leads invariably to this.

In terms of code complexity, this wasn’t just the case for our Squad; some very smart people have taken it (and continue to take it) to the extreme. The funny part is that, because dependency hell is so ubiquitous in Scala-land (which includes Java-land), we ended up using some of the projects that we deemed too complex for our codebase (e.g scalaz) via transitive dependencies.

Consider these randomly selected examples from some of the Scala libraries we’ve been using (and continue to maintain):

Strong Syntax (What is this file’s purpose, without being a theoretical physicist?)

Content Type (broke Github’s linter)

Abstract Table (Would you explain foreignKey’s signature to me?)

While still on the Scala happiness train, we read this post with great curiosity (originally posted here, but site is now down). I find myself wholeheartedly agreeing with it today.

Channels and goroutines have made our job so much easier

It’s not just the fact that channels and goroutines are cheaper in terms of resources, compared to threadpool-based Futures and Promises, resources being memory and CPU. They are also easier to reason about when coding.

To clarify this point, I think that both languages and their different approaches can basically do the same job, and you can reach a point where you are equally comfortable working with either. Perhaps the fact that makes it simpler in ‘Go’ is that there’s usually one limited set of tools to work with, which you use repeatedly and get a chance to master. With Scala, there are way too many options that evolve too frequently (and get superseded) to become proficient with.

Case study

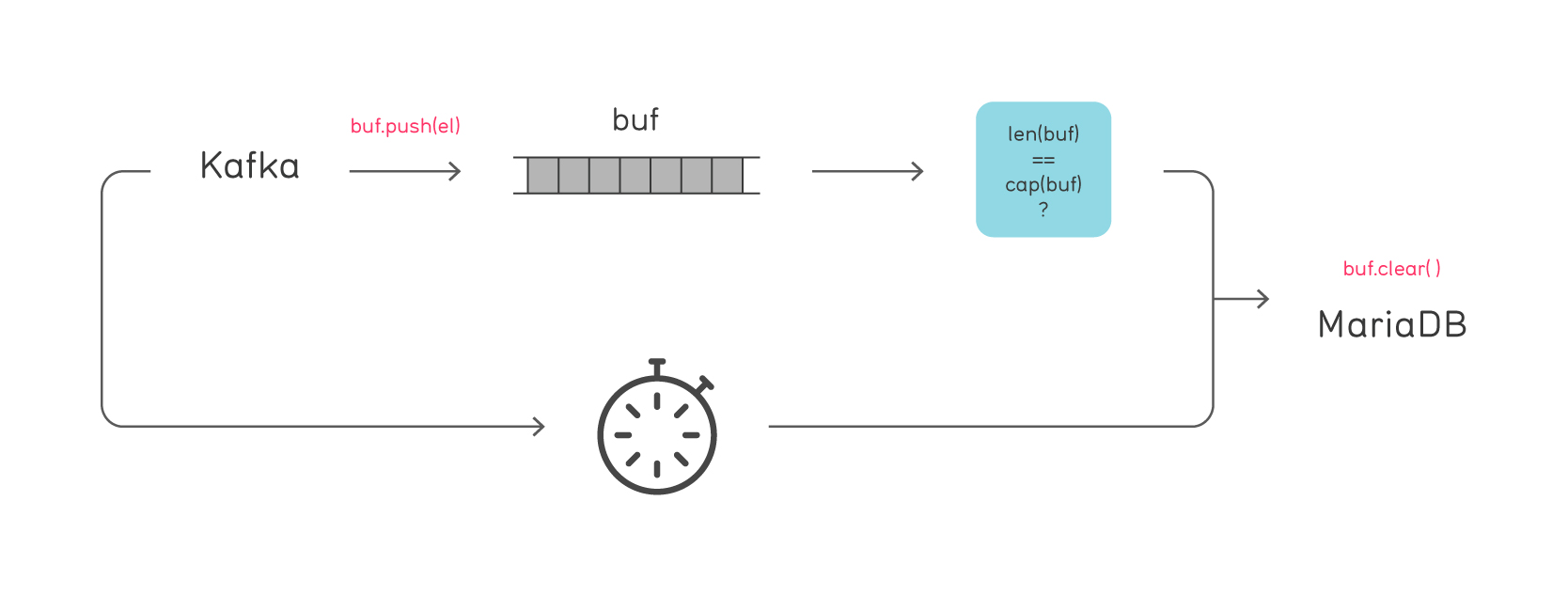

Recently, we’ve been struggling with an issue where we had to process some billing information.

The data came through a stream, and had to be persisted to a MariaDB database. As persisting directly was impractical due to the high rate of data consumption, we had to buffer and aggregate, and persist on buffer full or after a timeout.

First, we made the mistake of making the persist function synchronized. This guaranteed that buffer-full-based invocations would not run concurrently with timeout-based invocations. However, because the stream digest and the persist functions did run concurrently and manipulated the buffer, we had to further synchronize those functions to each other!

In the end, we resorted to the Actor system as we had Akka in the module’s dependencies anyway, and it did the job. We just had to ensure that adding to the buffer and clearing the buffer were messages processed by the same Actor, and would never run concurrently. This is just fine, but to get there we needed to; learn the Actor System, teach it to the newcomers, import those dependencies, have Akka properly configured in the code and in the configuration files, etc. Furthermore, the stream came from a Kafka Consumer, and in our wrapper we needed to provide a digest function for each consumed message that ran in a Future. Circumventing the issue of mixing Futures and Actors required extra head scratching time.

Enter channels.

buffer := []kafkaMsg{}

bufferSize := 100

timeout := 100 * time.Millisecond

for {

select {

case kafkaMsg := <-channel:

buffer = append(buffer, kafkaMsg)

if len(buffer) >= bufferSize {

persist()

}

case<-time.After(timeout):

persist()

}

}

func persist() {

insert(buffer)

buffer = buffer[:0]

}

Done; Kafka sends to a channel. Consuming the stream and persisting the buffer never run concurrently, and a timer is reset to timeout 100 milliseconds after no messages received.

Further reading; a few more illustrative channel examples:

Parallel processing with ordered output

A simple strategy for server-side backpressure

It compiles fast and runs fast

Go runs very fast.

Our Go microservices currently:

Build in 5 seconds or less

Test in 1 or 2 seconds (including integration tests)

Run in our CI infrastructure in less than half a minute (and we’re looking into it, because that’s unacceptable!), outputting a Docker container

Deploy (via Kubernetes) new containers in 10 seconds or less (key factor here being small images)

A feedback loop of one second on our daily struggle with computers has made us more productive and happy.

Microservice panacea: from dev-done to deployed in less than a minute on cheap boxes

We’ve found that Go microservices are a great fit for distributed systems.

Consider how well it fits with the requirements:

- Tiny-sized containers: our average Go docker container is 16.5MB, vs 220MB for Scala

- Low-memory footprint: mileage may vary; recently, we’ve had a major success when rewriting a crucial µs from Scala to Go and going from 4G to 300M for the worst-case scenario usage

- Fast starts and fast shutdowns: just a binary; no need to start a VM

For us, the fatter Scala images not only meant more money spent on cloud bills, but crucially container orchestration delays. Re-scheduling a container on a different Kubernetes node requires pulling the image from a registry; the bigger the image, the more time it takes. Not to mention, pulling the latest image locally on our laptops!

Last but not least: tooling

In the Red Squad, we have a very diverse choice of IDEs:

Go plays really well with all of them! Tools are also steadily improving over time, and new tools are created often.

My personal favourite item in our little ‘Go’ rebellion: for the first time ever, we make our own tooling!

Here’s a selection of our open source projects we’re currently using at work:

Kafka tool for consuming, producing and getting info about Kafka topics; composes nicely with jq.

Kubernetes Mirror; bash/zsh autocompletion for kubectl parameters (e.g. pod names).

MySQL pipe; sends queries to one, many or all your MySQL instances, local or remote, or behind SSH tunnels, and outputs conveniently for further processing. Composes nicely with chart; another tool we’ve written for quick ad-hoc charting.

Real-time and after-the-fact visualization for Kafka-based distributed systems.

So… Go all the things?

Not so fast. There’s much we’re not wise enough to comment on yet. Movio’s use cases are only a subset of a very long and diverse list of requirements.

Choose based on your use case. For example, if your main focus is around data science you might be better off with the Python stack

Depending on the ecosystem that you come from, a library that you’re using might not exist or not be as mature as in Java. For example, the Kafka maintainers are providing client libraries in Java, and the Go versions will naturally lag behind the JVM versions

Our microservices generally do one tiny specific thing; when we reach a certain level of complexity we usually spawn new microservices. Complex logic might be cumbersome to express with the simple tools that Go provides. So far, this has not been a problem for us

Golang is certainly a good fit for our squad! See how it “Goes” for you :P