TL;DR

In this blogpost, I introduce the ostinato project: a Chess engine written in Scala.

It’s not the fastest engine around, nor the hardest AI to beat. However, it enables some use cases that I haven’t found good free online sources for, like parsing notations into matches, converting between notations, playing against the AI from a given step in a parsed match, as well as the ability to solve chess puzzles and problems via elegant one-liners on the Scala REPL.

By cross-compiling into JS using ScalaJS, the same Scala code can run in the browser as a JavaScript library, which is great for two reasons:

- the tools can be available online for free with Github service quality

- JS devs can use the library without any Scala knowledge

There is an ostinato Docker image available on Docker Hub (or it can be built locally) which exposes the same API as the JS library via an Akka HTTP server.

Because ostinato is 100% stateless, it’s a perfect candidate for Kubernetes deployments: each individual API request (e.g. an AI move) can be load balanced over a set of pods, and pod count can be auto-scaled based on CPU load average. This makes it attractive for AI research and as a backend for chess sites.

Project links

Demos

Play a Chess Match against the AI.

Tool to paste any chess match in any known notation and browse through the moves via Chessboard. Also play from any board state against the AI, or convert to any other notation.

Convert any pasted chess match between the following notations: PGN, Algebraic, Figurine, Coordinate, Descriptive, ICCF, Smith and FEN (with variations).

Two AI’s playing each other (making random moves).

Meta

I’ve recently upset some good people of the Scala community with this blogpost that became a language war. Partly, for me, working on this blogpost means showing some of the nice use-cases Scala enables, in particular one that Golang can’t do: solving complex domain-specific problems with elegant one-liners. Hopefully we can focus on the engineering this time. Sorry that I didn’t foresee or do more to prevent this on the previous blogpost.

Solving puzzles in the REPL

A quite unique feature of ostinato is that it leverages the Scala differentials in terms of succintness and elegance for actually solving problems. As a result, it becomes feasible to solve chess brain teasers directly in the REPL with only a few one-liners.

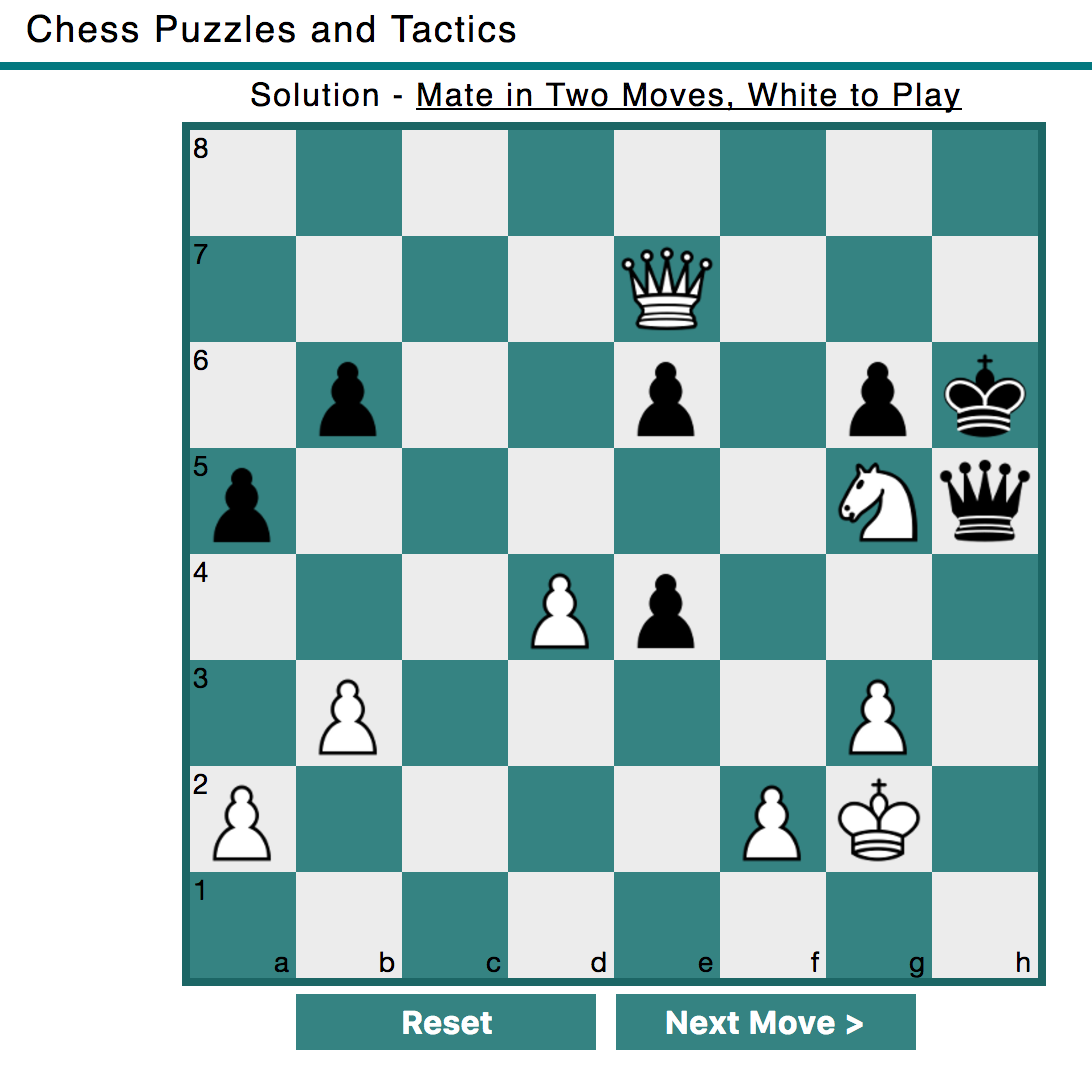

Let’s try a checkmate in two moves. Here’s an example puzzle:

White moves first and it should make checkmate in the second move.

Let’s solve it!

First, we need to compile the jar so we can play with it in the REPL. This should be easy: (alternatively, just download the latest jar from Releases)

$ sbt pack

We should be able to start a REPL with the ostinato jar in the classpath (the exact path could change over time so just ls the folder and find the ostinato_2.12-*.jar):

$ scala -cp target/pack/lib/ostinato_2.12-1.0.2.jar

Import the core, so we can use the chess classes:

scala> import ostinato.chess.core._

import ostinato.chess.core._

OK. Let’s generate a ChessBoard identical to the one in the puzzle:

scala> val b = ChessGame.fromGridString(

"""........

|....♕...

|.♟..♟.♟♚

|♟.....♘♛

|...♙♟...

|.♙....♙.

|♙....♙♔.

|........""".stripMargin, turn = WhiteChessPlayer).get.board

b: ostinato.chess.core.ChessBoard =

........

....♕...

.♟..♟.♟♚

♟.....♘♛

...♙♟...

.♙....♙.

♙....♙♔.

........

All the ChessGame.from... methods return a Try[ChessGame], because parsing could fail. In this case, I know it’ll work so I just .get, and get the board from it.

Note that the Unicode symbols were made with the assumption of black foreground and white background. In the REPL, this is often times backwards. This might confuse you as to which colour is which. Use this as a safe copy-paste.

We’re gonna need to ask ostinato to be optimistic. If we calculate all actions on this board, ostinato will include White resigns and White claims draw, which we’re not interested in. Same will apply for the next moves. Let’s create a ChessOptimisations instance and pass it around:

scala> val o = ChessOptimisations.beOptimistic

Here’s the meaty part. We need to express the following statement in code:

“Find the actions such that for whichever following action, there’s at least one follow-up checkmate”

If the puzzle was constructed properly, there should be only one action that satisfies those conditions:

scala> b.doAllActions(o).filter(

_.doAllActions(o).forall(

_.doAllActions.exists(

_.isLossFor(BlackChessPlayer)

)

)

)

res1: scala.collection.immutable.Set[ostinato.chess.core.ChessBoard] =

Set(.....♕..

........

.♟..♟.♟♚

♟.....♘♛

...♙♟...

.♙....♙.

♙....♙♔.

........)

Yes! There’s exactly one ChessBoard in the resulting Set!

Let’s extract the action so we can apply it to our ChessBoard. That can be accomplished by appending .head.history.head.action.get to our previous line (i.e. getting the first action in the history).

ChessAction has a nice toString implementation.

scala> val a = res1.head.history.head.action.get

a: ostinato.chess.core.ChessAction = White's Queen moves to f8

Let’s apply the action on the board. Not all actions can be applied on a board, so doAction returns an Option[ChessBoard]. For brevity we’ll just .get it here:

scala> val b2 = b.doAction(a).get

b2: ostinato.chess.core.ChessBoard =

.....♕..

........

.♟..♟.♟♚

♟.....♘♛

...♙♟...

.♙....♙.

♙....♙♔.

........

Lastly, let’s see the full action history.

We’ll have to:

- pick any black action (

headin this case) - filter the white checkmate action

- retrieve the action history

- history is stored backwards so we’ll have to reverse it to read it properly

scala> b2.doAllActions(o).head.doAllActions.

filter(_.isLossFor(BlackChessPlayer)).head.

history.flatMap(_.action).reverse

res5: List[ostinato.chess.core.ChessAction] =

List(

White's Queen moves to f8,

Black's King captures White's Knight,

White's Queen moves to f4

)

Profit! Do compare with the puzzle site, but the solutions match.

Within the REPL, ostinato becomes a swiss-army knife for chess-related queries.

Taking the red pill

If you’re gonna be playing around with advanced cases in the REPL, you’ll probably need some time to get used to the code (you should know Scala; no chance otherwise). These examples, the Scaladoc and the hundreds of tests are good starting points, but I’d be happy to help you on my spare time so let me know; my details are at the top of the page and/or post a comment below. There’s a very reduced set of voodoo code overall, and I’m not proud of it (anymore, that is).

In the browser: ostinato.js

Although ~97% of the ostinato codebase is written in Scala, it leverages ScalaJS as a facade to enable JS use cases. By cross-compiling the code, ScalaJS produces an ostinato.js file. This strategy makes all the free tools feasible.

Most of the demos also leverage the popular and solid ChessboardJS library for UI. Because ChessboardJS’ notation conventions make a lot of sense, ostinato’s API was exposed in a way that is compatible with it.

The best part of JS support is that JS developers can use the chess engine without any Scala knowledge.

Just download the latest js file in the releases section.

Using ostinato.js is really simple and easy. For a great working intro, check the auto-play demo.

Here’s the meaty part. You’ll have to pardon my js, but I think it should be quite clear:

<script>

var boardUi = null

var initialBoard = "rnbqkbnr/pppppppp/8/8/8/8/PPPPPPPP/RNBQKBNR w KQkq - 0 1"

var board = initialBoard

var init = function() {

var update = function() {

aiMove = ostinato.chess.js.Js().randomAiMove(board)

board = (!aiMove.success || aiMove.isCheckMate ||

aiMove.isDraw) ? initialBoard : aiMove.board

boardUi.position(board)

window.setTimeout(update, 600)

}

boardUi = ChessBoard('board', { moveSpeed: 'fast' })

boardUi.start()

update()

}

</script>

The only ostinato line in there is ostinato.chess.js.Js().randomAiMove(board). The rest is ChessboardJS and plain JavaScript.

Here’s what’s available at the moment from JavaScript: Js.scala

From here, you should be able to go to the other examples. If you’re interested in developing an advanced use case, I’d be happy to help you on my spare time. Find my contact details at the top of this page and/or post a comment below.

Server-side

Running ostinato on the JVM has several pros:

- It runs faster than its ScalaJS counterpart

- Because ostinato is 100% stateless, one server can play several games at a time

- No high CPU usage on the client; responsiveness is up to the server

Via sbt

Try starting the server via sbt:

$ sbt ostinatoJVM/run

You can check if it’s working by trying the healthcheck:

(which could be used as a livenessProbe on a Kubernetes deployment)

$ curl localhost:51234/healthcheck

OK!

Or get an initial board to start playing from:

$ curl localhost:51234/initialBoard

{"board":"rnbqkbnr/pppppppp/8/8/8/8/PPPPPPPP/RNBQKBNR w KQkq - 0 1"}

And then make the computer play from it:

$ curl localhost:51234/randomAiMove -d \

'{"board":"rnbqkbnr/pppppppp/8/8/8/8/PPPPPPPP/RNBQKBNR w KQkq - 0 1"}' \

-H "Content-Type: application/json"

{

"success":true,

"isCheck":false,

"isDraw":false,

"board":"rnbqkbnr/pppppppp/8/8/8/5N2/PPPPPPPP/RNBQKB1R b KQkq - 1 1 7163",

"isCheckmate":false,

"action":"Nf3"

}

Let’s try something more fun

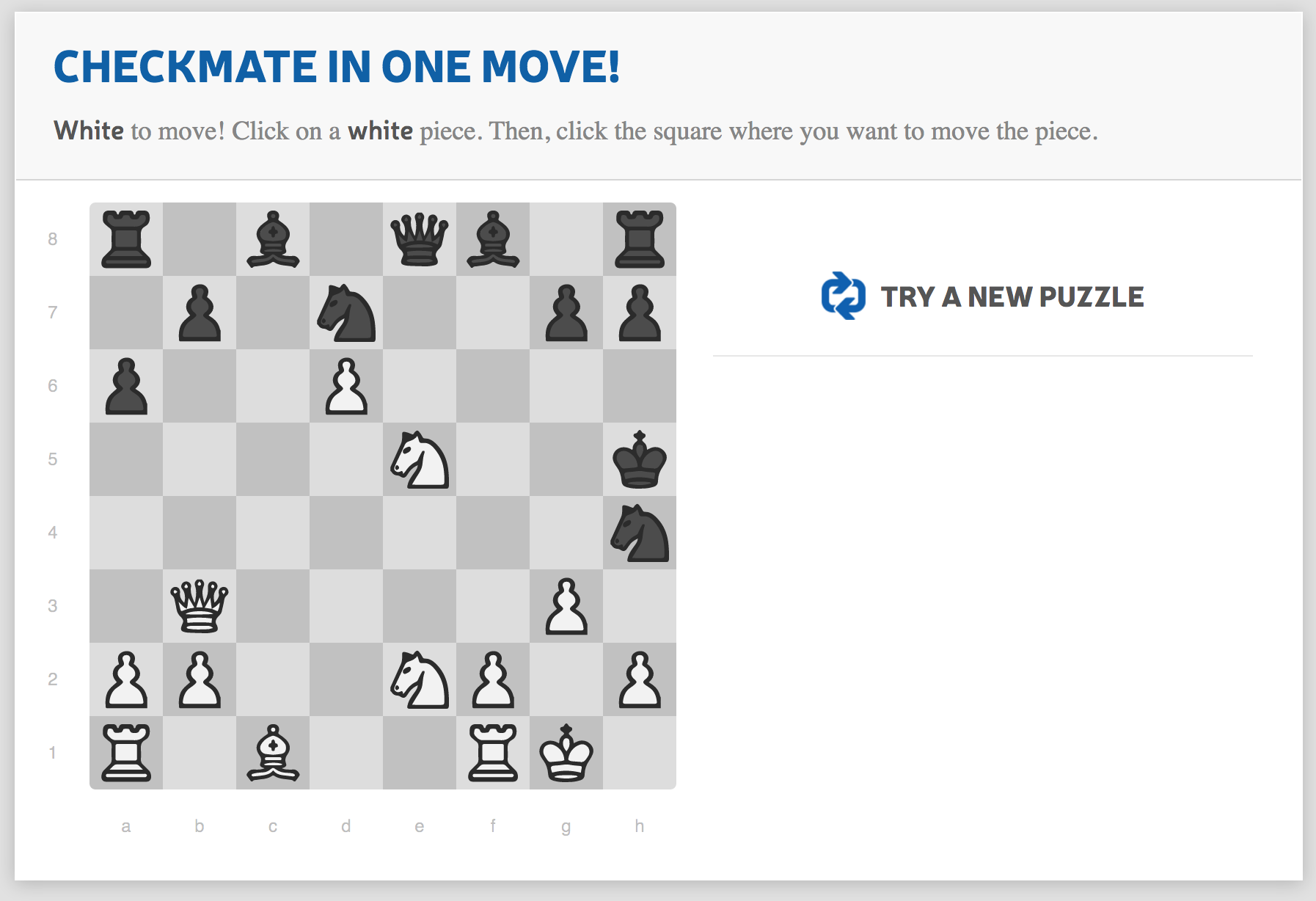

This site provides “mate in one move” puzzles. Here’s one example:

Ostinato server expects the input boards in “ostinato notation”, which is simply FEN notation plus (optionally) the history in ICCF notation.

I’m too lazy to translate a board to FEN manually, so I looked around (for way longer that it would have taken me to just do it manually -.-) and I found this Android app that OCRs the board and producess the FEN, which was:

r1b1qb1r/1p1n2pp/p2P4/4N2k/7n/1Q4P1/PP2NP1P/R1B2RK1 w - - 0 1

I would expect the basic AI to want to win as soon as possible, so let’s see if it finds the checkmate:

$ curl localhost:51234/basicAiMove -d \

'{"board":"r1b1qb1r/1p1n2pp/p2P4/4N2k/7n/1Q4P1/PP2NP1P/R1B2RK1 w - - 0 1"}' \

-H "Content-Type:application/json"

{

"success": true,

"isCheck": true,

"isDraw": false,

"board": "r1b1qb1r/1p1n2pp/p2P4/4N2k/6Pn/1Q6/PP2NP1P/R1B2RK1 b - - 0 1 7374",

"isCheckmate": true,

"action": "g4+"

}

Luckily, the AI didn’t disappoint me :). It recommended advancing the pawn on the g file (above the white king), and it seems adamant that it’s a checkmate.

From a geeky perspective, I find it useful to have this decoupled mini-tool at my disposal.

Also, I recently switched the JSON engine to spray-json which patiently reminded me of the JSON object names and types I was supposed to provide to the API call until I got them right. Props to Mathias. If somebody could please ask him how can I unmarshal the request’s JSON payload when the Content-Type is not application/json, I’d really appreciate it. I’ve asked around on Gitter and SO and couldn’t get a good solution.

Playing a demo game using the JVM as back-end

Simply use the provided demo chess game and add the following query parameters:

useServer=localhost:51234 // location of your ostinato back-end

depth=1 // complexity of the AI (from 0, but 3 is already slow)

debug=1 // optional: logs AI rationale to STDOUT

e.g. https://marianogappa.github.io/ostinato-examples/play?useServer=localhost:51234&depth=1

I’m not a particularly good chess player, but depth 3 beats me. I was so happy when I reached that milestone <3

Docker

You can start an ostinato container right from Docker Hub with:

$ docker run -p 51234:51234 marianogappa/ostinato:latest

Once it’s up, you can try the healthcheck and other examples described above. Note that Docker may not open the port on localhost; this depends on your Docker installation.

If you want to experiment with the code and build the image locally (for which you will need sbt & Docker), you can use the provided script on the root folder:

$ ./docker-build.sh

The script will kindly ask you to run sbt packArchiveZip if you haven’t done so, or if the last produced artifact was last modified half and hour ago or more.

The script always builds the ostinato image with the tag latest. If you want to specify a custom tag, you can do it like this:

$ TAG=v1.2.3 ./docker-build.sh

Kubernetes

As previously mentioned, ostinato is 100% stateless. The server doesn’t save any state from previous requests, and all the information necessary to respond to a request is present in the request itself.

This means that:

- Any given ostinato server can satisfy requests from multiple games

- A game can be played by issuing requests to multiple ostinato servers

Thus, load balancing strategies become very simple with ostinato. Some popular solutions right now are:

At least with Kubernetes, there’s also the possibility of dynamically increasing the number of ostinato container replicas when the CPU usage exceeds a given threshold; this is called auto-scaling.

Ostinato doesn’t use any disk and doesn’t have any special configurations so you don’t need to mount anything. As a JVM application, though, it’s not the cheapest in terms of CPU, memory, and image size. It’s using the smallest base image I could find that has a JVM: the alpine-java one.

Here’s a deployment manifest to get you started:

---

apiVersion: extensions/v1beta1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: ostinato

spec:

replicas: 2

template:

metadata:

labels:

name: ostinato

spec:

containers:

- name: ostinato

image: ostinato:latest

imagePullPolicy: IfNotPresent

resources:

requests:

cpu: 500m

memory: 128Mi

limits:

cpu: 4000m

memory: 512Mi

livenessProbe:

initialDelaySeconds: 15

httpGet:

path: "/healthcheck"

port: 51234

ports:

- name: external

protocol: TCP

containerPort: 51234

The rationale behind low requests and high limits is that ostinato aggresively parallelises requests but they arrive infrequently, so bursts of usage can be multiplexed on the same Kubernetes minion. Mileage may vary; greater depths are memory hungry.

You’ll need a service to expose the server to your client code. Here’s a service manifest:

---

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: ostinato

spec:

selector:

name: ostinato

ports:

- name: external

port: 51234

targetPort: 51234

Apply both manifests with kubectl:

$ kubectl apply -f ostinato-deployment.yml

$ kubectl apply -f ostinato-service.yml

Your ostinato instances should be reachable via the Kubernetes proxy API, e.g.:

https://kubernetes_domain_name/api/v1/proxy/services/ostinato:51234/healthcheck

Follow the auto-scaling guidelines for dynamic scaling. Here’s a quick trick:

$ kubectl autoscale deployment ostinato --min=2 --max=5

Developing ostinato and final thoughts

Developing ostinato was an amazing experience. I got to learn a lot about chess, a lot about Scala, a lot about OSS and a lot about software engineering.

I believe ostinato has enabled some free and open source chess-related use cases that were unavailable before; if you find them useful I’d be very happy to hear about it.

One thing I wanted to learn was how much I was profiting from OOP (after reading Lawrence Krubner’s famous OOP blogpost). Seeing chess as a poster child for OOP, I started the library as a “turn-based game library” rather than just a “chess library”, where ChessGame extended Game and ChessAction extended Action and so on. The resulting code scares me still.

Another thing I’ve learnt is that OOP and immutable design meet the hardware in a blurring mist, and while the succintness and elegance can aid in real-life problem solving, they also hide big O complexity greatly. At some inflection point, the indirection trade-off is not worth it. While not proud about it, I must link you to some compromises I’ve made to gain acceptable response times.

During extensive refactorings, I’ve learnt to love IntelliJ’s renaming features. If just for that, and with its shortcomings, I think IntelliJ has raised the bar in that respect. I’ve found it as convenient as Sublime Text’s multiple cursors.

I’ve learnt to beware of implicits. While they enable important use cases, they are used way more than they should be. I wasn’t able to completely get rid of them in the ostinato codebase (partly because I was bound by the superclass’ method signatures; thanks OOP), but overall I believe I’ve tamed the beast and learnt a valuable lesson.

Big thank you to Cecilia Fladung for designing the logo, and to the elite reviewers: @echojc, @therealplato and @chris_d_barret.

Thank you for reading this blogpost. KISS!