We saved $50k/y with a tiny Go microservice coded in a Hackathon

NOTE: my original blogpost was published in the Movio blog. I’ve had to steal it because it went offline for a while, the link sometimes 404s, and they’ve broken some links. I don’t want it to be lost. The following content is unchanged from the original.

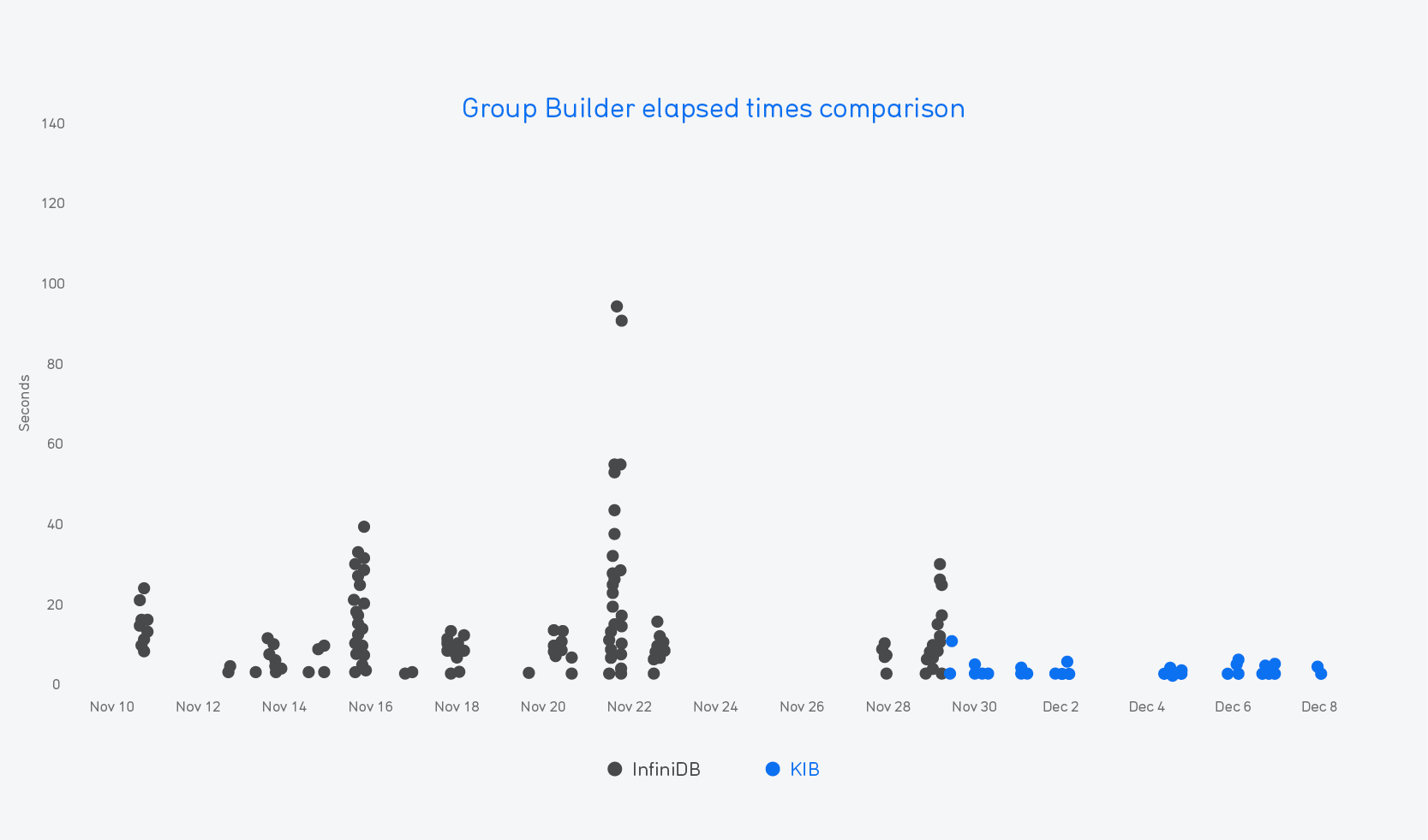

In the past few weeks we’ve rolled out a Go microservice called “KIB” to production, which reduced a huge portion of the infrastructure necessary for Movio Cinema’s core tools: Group Builder and Campaign Execution. In doing this, we saved considerable AWS bills, after-hours and office-hours support bills, significantly simplified our architecture and made our product 80% faster on average. We wrote KIB on a Hackathon.

Despite the fact that the domain-specific components of this post don’t apply to every dev team, the success of applying the guiding principles of simplicity and pragmatism driving our decision-making process felt like a story worth sharing.

Group Builder

Movio Cinema’s core functionality is to send targeted marketing campaigns to a cinema chain’s loyalty members. If you’re a member of a big cinema chain’s loyalty program, wherever you are in the world, chances are the emails you’re getting from it come from us.

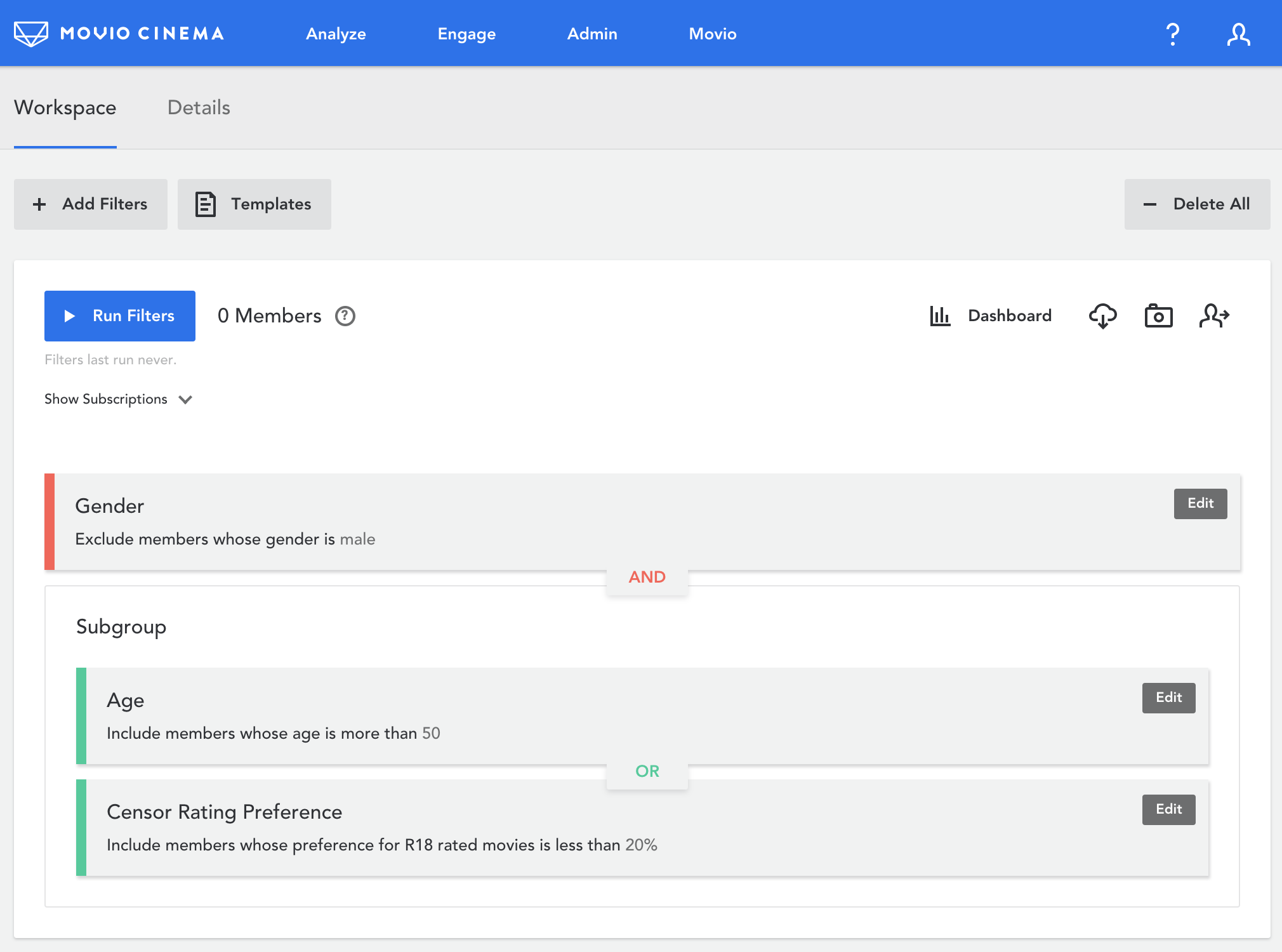

Group Builder facilitates the segmentation of loyalty members by the construction of groups of filters of varying complexity over the cinema’s loyalty member base.

Marketing teams around the world build the perfect audiences for their marketing campaigns using this tool.

The Group Builder algorithm

By using this algorithm, an arbitrarily complex set of filters can be solved with a single SQL query. Note that it’s domain-agnostic; you can use this strategy for filtering any set of elements.

Constraints

A Group Builder group can have any number of filters.

Filters can be grouped together in an arbitrary number of sub-groups.

Strictly for UI/UX reasons, sub-groups can be nested only once (i.e. up to sub-sub-groups).

Filters and groups operate against each other using Algebra of Sets.

Each filter can either include or exclude set elements, set elements being loyalty members. The UI shows filters as green when they include members, and red when it excludes members.

Here’s the SQL strategy

This would be the final query for the Group Builder UI image above; note that the 3 filter subqueries represent the 3 filters shown in the image:

SELECT

t.loyaltyMemberID,

MAX(CASE WHEN t.filter = 1 THEN 1 ELSE 0 END) AS f1,

MAX(CASE WHEN t.filter = 2 THEN 1 ELSE 0 END) AS f2,

MAX(CASE WHEN t.filter = 3 THEN 1 ELSE 0 END) AS f3

FROM (

(

SELECT loyaltyMemberID, 1 AS filter FROM … // Gender

) UNION ALL (

SELECT loyaltyMemberID, 2 AS filter FROM … // Age

) UNION ALL (

SELECT loyaltyMemberID, 3 AS filter FROM … // Censor

)

) AS t

GROUP BY t.loyaltyMemberID

HAVING

f1 = 1 // = 1 means "Include"

AND (

f2 != 1 // != 1 means "exclude"

OR

f3 = 1

) // Parens equate to subgroups in the UI

Each sub-query in the UNION section selects the set of loyalty members after applying each filter in the group. The result set of the UNION (before the GROUP BY) will have one row per member per filter. The GROUP BY together with the AGGREGATE FUNCTIONs in the main SELECT section provide a very simple way to replicate the set algebra specified in the Group Builder UI, which you can see cleanly separated in the HAVING section.

The limits of MySQL

The Group Builder algorithm worked really well in the beginning, but after some customers reached more than 5 million members (and 100 million sales transactions) the queries simply became way too slow to be able to provide timely feedback.

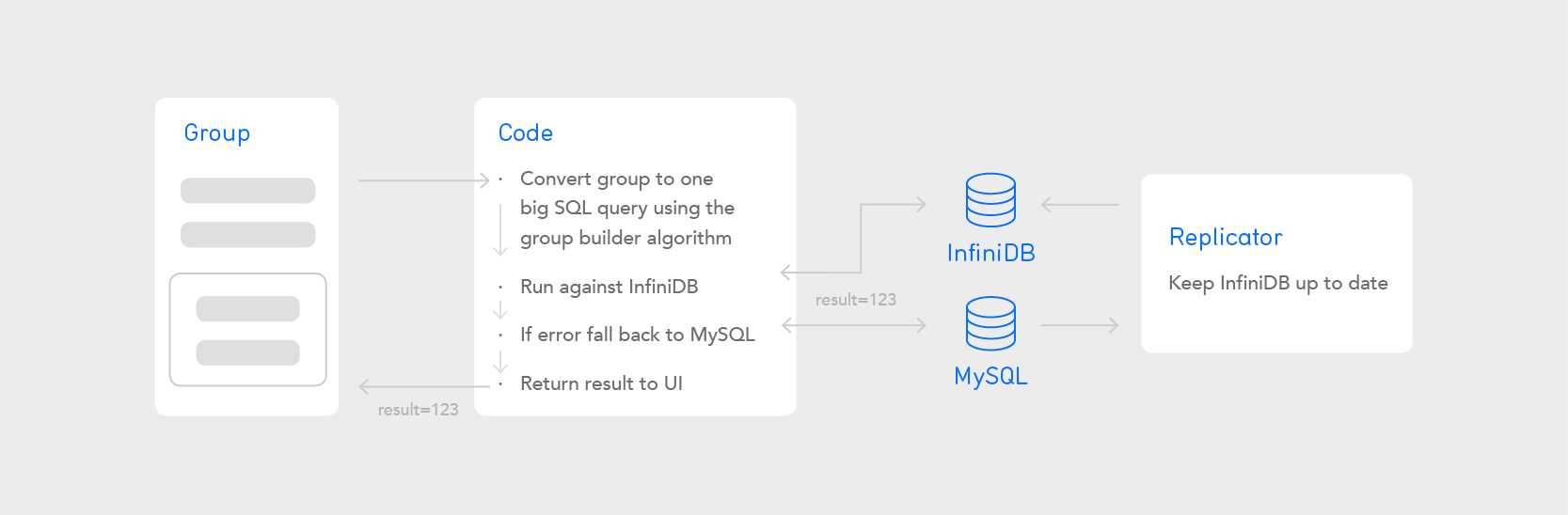

We needed an option that was fast but didn’t require re-architecting our whole product. That option was InfiniDB. This was 2014.

InfiniDB: a magic drop-in replacement

InfiniDB was a MySQL almost-drop-in replacement that stored data in columnar format. As such, and given our queries were rarely involving many fields, our InfiniDB implementation was a big success. We didn’t stop using MySQL; instead we replicated data to InfiniDB in near real-time.

Super-slow groups were fast again! We rolled out our InfiniDB implementation to all big customers and saved the day.

The cons of our implementation of InfiniDB

Despite the success of our solution, it wasn’t without significant costs:

The InfiniDB instances required a lot of memory and CPU to function properly, so we had to put them on i3.2xlarge EC2 instances. This was very expensive (~$7k per annum), considering we didn’t charge extra for InfiniDB-powered Movio Cinema consoles.

InfiniDB didn’t have a master-slave scheme for replication (except for this), so we had to build our own custom one. Unfortunately, table name-swapping sometimes got some tables corrupted and we had to re-bootstrap the whole schema to come back up online, a process that could take several hours.

We had a recurring bug where some complex count queries would just return 0 results on InfiniDB, but the same query on MySQL wouldn’t. It was never resolved.

Even though InfiniDB was much faster than MySQL, we still saw some slow running groups for every big customer every week throughout 2017.

The company behind InfiniDB sadly had to shutdown and was eventually incorporated into MariaDB (now MariaDB ColumnStore); this meant no updates nor bugfixes.

InfiniDB had no substantial community, so it was really hard to troubleshoot any issues. There were only 120 questions on StackOverflow at the time of this writing.

Research time

During the winter of 2017 we had an upcoming Hackathon, so three of us decided to do a little research on how to create an alternative solution for Group Builder.

We found that, even in slow-running groups, most of the filters were relatively simple and fast queries, and retrieving the resulting set of members was incredibly fast as well (~one million per second). The slowness was mostly in the final aggregation step, which could produce billions of intermediate rows on groups with many filters.

However, a few filters were slow no matter what. Even on fully indexed query execution plans they still had to scan over half a billion rows.

How could we circumvent these two issues with a simple solution achievable in a day?

Hackathon idea: the KIB project

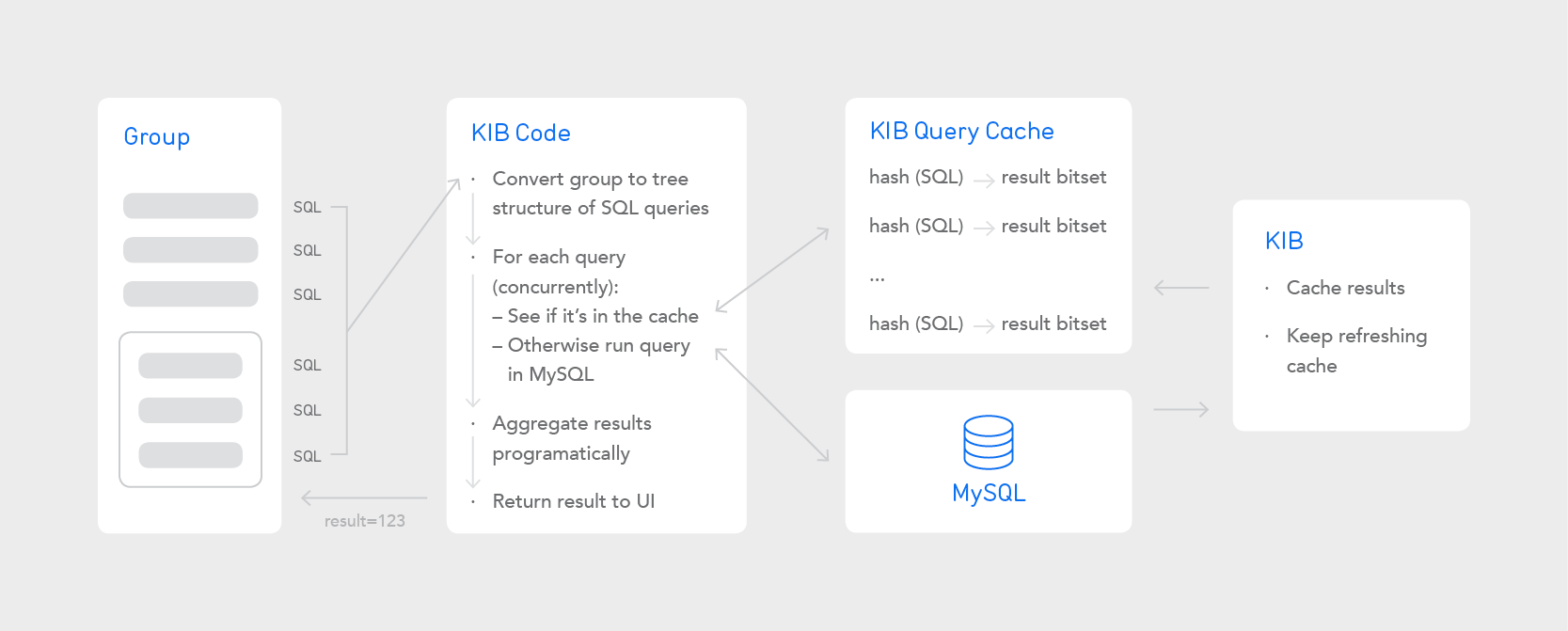

Our solution was:

Reviewing all slow filters for quick wins (e.g. adding/changing indexes, reworking queries)

Running every filter as a separate query against MySQL concurrently, and doing the aggregation programmatically using sparse bitsets

Caching filter results for a number of minutes to minimise the time recalculating long-running queries, given the repetitive usage pattern shown by our customers

After the Hackathon, we quickly added two planned features that covered outstanding problematic cases:

Refreshing caches automatically, to make most frequently used filters and slow-running ones very quick at all times.

Pre-caching on startup based on usage history.

We packed these features into a tiny Go microservice called KIB and shipped it onto a c4.xlarge EC2 instance (<$3k per annum). While before we had one InfiniDB instance on a i3.2xlarge for each customer, in this case we put all customers on the same single c4.xlarge instance.

We did add a second instance for fault tolerance, and it was a fortunate decision, because that very week our EC2 instance died. Thanks to our Kubernetes cluster implementation, the KIB instance quickly restarted on the second healthy node and no customers were impacted. In contrast, when our InfiniDB nodes died, re-bootstrapping would sometimes take hours. Note, however, that this was not an intrinsic problem of InfiniDB itself, but of our custom replication implementation of it.

Why Go?

The long answer to that question is described in this blogpost. In short, we’ve been coding in Go for about a year, and it has noticeably reduced our estimations and workload, made our code much simpler, which in turn has indirectly improved our software quality, and in general has made our work more rewarding.

Here are the key bits of the KIB Go code with only a few details elided:

An endpoint request represents a Group Builder group to be run, and the group is represented as a tree of SQL queries. It looks somewhat like this:

type request struct {

N SQLNode `json:"node"`

}

type SQLNode struct {

SQL string `json:"sql"`

Operator string `json:"operator"`

Nodes []SQLNode `json:"nodes"`

}

This is the function that takes the request and resolves every SQL in the tree to a bitset:

func (r request) toBitsets(solver *solver) (*bitsetWr, error) {

var b = bitsetWr{new(tree)}

b.root.fill(r.treeRoot, solver) // runs all SQL concurrently

solver.wait() // waits for all goroutines to finish

return &b, solver.err

}

This is the inner function that deals with the tree structure; running “solve” on every node:

func (t *tree) fill(n SQLNode, solver *solver) {

if len(n.Nodes) == 0 { // if leaf

t.op = n.Operator

solver.solve(n.SQL, t) // runs SQL; fills bitset

return

}

t.nodes = make([]*tree, len(n.Nodes)) // if group

for i, nn := range n.Nodes {

t.nodes[i] = &tree{}

t.nodes[i].fill(nn, solver)

}

}

And this is the inner function that runs the SQL (or loads from cache) concurrently:

func (r *solver) solve(sql string, b *tree) {

r.wg.Add(1)

go func(b *tree) { // returns immediately

defer r.wg.Done()

res, err := r.cacheMaybe(sql) // runs SQL or uses cache

if err != nil {

r.err = err

return

}

b.bitset = res

}(b)

}

There are about 50 more lines for solving the algebra and 25 more for the basic caching, but these three snippets are a representative example of what the KIB code looks like.

The snippets show some intermediate concepts: tree traversal, green threads, bitset operations and caching. While not that uncommon, what I’ve rarely seen in practice is an implementation of all these things solving a real business problem within a day’s work. We don’t think we would have been able to pull this off in any other language. I’ll explain why we think so in the conclusion.

Results

The results of our project were extremely gratifying.

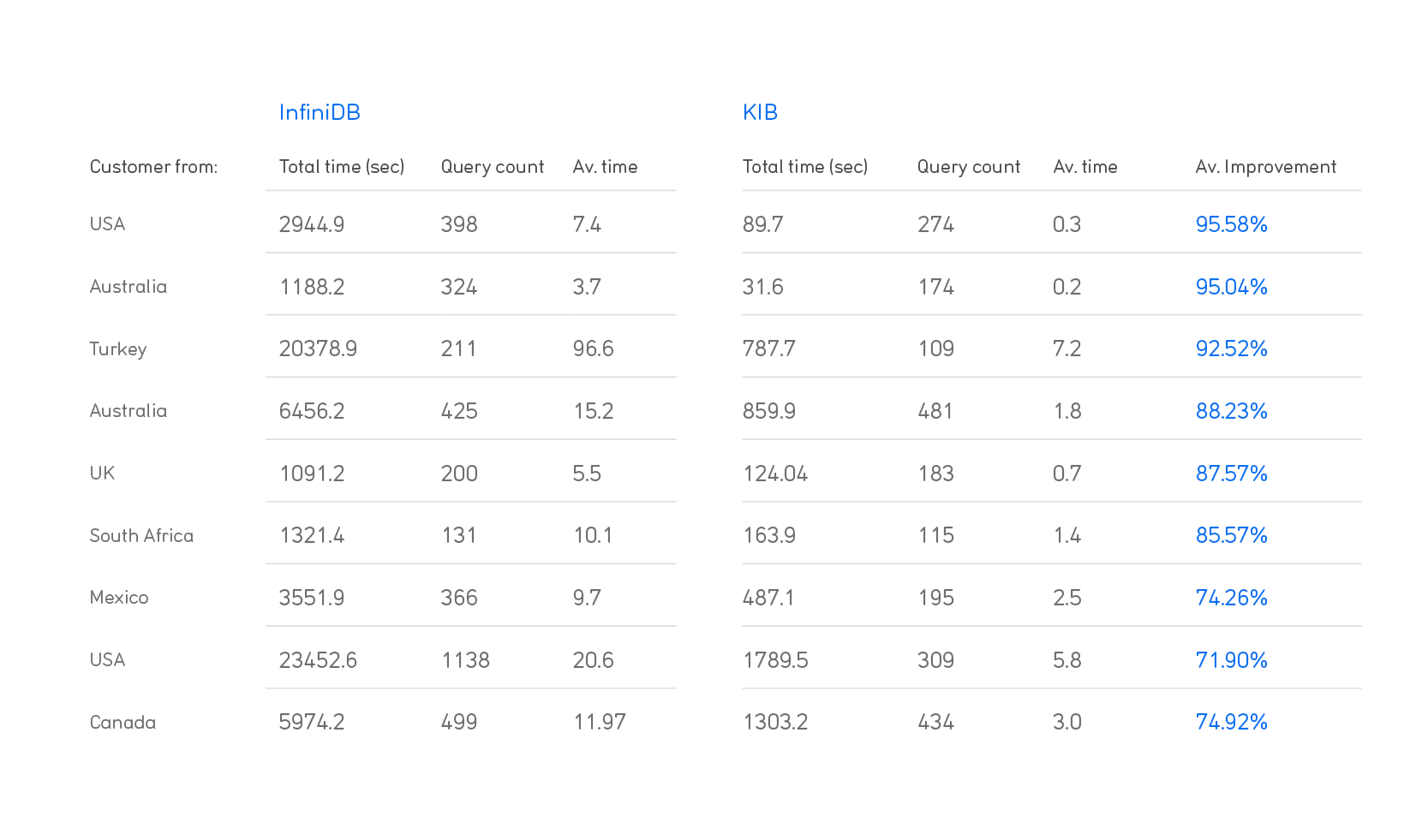

In financial terms, we saved $31.000 yearly in AWS bills and $4.000 yearly in after-hours support. In-office support & maintenance probably costed more than the previous ones combined in the last year, but these are not easily quantifiable in dollar value. Note that our InfiniDB-based solution has undergone yearly rewrites (we’ve had to rewrite our InfiniDB solution in 2015 and again in 2016 since our original 2014 implementation). By my calculation, we will save more than $50,000 this year and a similar amount every year going forward.

In terms of speed, here’s a week-on-week table of results for 9 of our biggest customers (we’ve replaced the actual names with their countries of origin):

For some customers, this upgrade meant not waiting for Group Builder anymore, as it was the case for this USA customer:

Globally, it was an 81% average improvement in group run times; an average constructed from every single Group Builder group ran on those weeks, not from a sample. That really exceeded our own expectations.

For us devs, replacing our complex custom replication implementation of InfiniDB that kept us up at night every other week with such a tiny and simple Go microservice we built on a Hackathon is the greatest gift.

Conclusions

Throughout the Hackathon, we spent the day researching, designing and coding, and no more than half an hour debugging. We didn’t have dependency issues. We didn’t have issues understanding each other’s code, because it looked exactly the same and just as simple. We fully understood the tools we were using, because we have been using the same bare bone building blocks for a year. We didn’t struggle with debugging, because the only bugs we had were silly mistakes that were either found early by the IDE’s linter or clearly explained by the compiler with error messages written for humans. All of this was possible thanks to the Go language.

KIB is in production today on all major customers, and it’s barely using a few hundred MB of RAM per customer and sharing 4 vCPUs among all of them. Even though we aggressively parallelised SQL query execution and bitset operations, we had no issues at all related to this: no “too many connections” to MySQL, no bugs related to concurrency, etc; not even while writing it. We did have one pointer-related bug and one silly tree traversal edge case; we’re human.

What’s the lesson learned here? My lesson learned is the power and value of simplicity. Even within the simplicity of Go, we went with the simplest (not the easiest) possible subset of it: we didn’t use channels, interfaces, panics, named returns, iotas, mutexes (we did have one WaitGroup for the one set of goroutines). We only used goroutines and pointers where necessary.

Thanks for reading this blogpost. KISS!