Let's build a SQL parser in Go!

TL;DR

This article aims to be the simplest introduction to constructing an LL(1) parser in Go, in this case for parsing SQL queries. It assumes minimal programming competence (functions, structs, ifs and for-loops).

Here’s the complete parser repository if you want to skip to results:

github.com/marianogappa/sqlparser

Simplification disclaimer

To make things simple we’re gonna descope sub-selects, functions, complex nested expressions and other features that all SQL flavours support. Those features get really involved quickly with the strategy we’re gonna use.

1-minute theory lesson

A parser has two parts:

Lexical Analysis

Let’s define it by example. “Tokenising” the following query:

SELECT id, name FROM 'users.csv'

Means extracting the “tokens” that form this query. The result of the tokeniser would be something like:

[]string{"SELECT", "id", ",", "name", "FROM", "'users.csv'"}

Syntactic Analysis

This part is where we actually look at the tokens, make sure they make sense and interpret them to construct some product struct that represents the query in a way that is convenient for the application that is gonna use it (e.g. for executing the query, colour highlighting it). After this step, we’d end up with something like:

query{

Type: "Select",

TableName: "users.csv",

Fields: ["id", "name"],

}

There are a lot of ways in that parsing can fail, so it would be convenient to do the two steps at the same time and stop as soon as something goes wrong.

Strategy

We’ll define a parser that looks like this:

type parser struct {

sql string // The query to parse

i int // Where we are in the query

query query.Query // The "query struct" we'll build

step step // What's this? Read on...

}

// Main function that returns the "query struct" or an error

func (p *parser) Parse() (query.Query, error) {}

// A "look-ahead" function that returns the next token to parse

func (p *parser) peek() (string) {}

// same as peek(), but advancing our "i" index

func (p *parser) pop() (string) {}

Intuitively, what we would do first is to “peek() the first token”. In a basic SQL grammar, there are only a few valid initial tokens: SELECT, UPDATE, DELETE, etc; anything else is an error already. The code would look something like:

switch strings.ToUpper(parser.peek()) {

case "SELECT":

parser.query.type = "SELECT" // start building the "query struct"

parser.pop()

// TODO continue with SELECT query parsing...

case "UPDATE":

// TODO handle UPDATE

// TODO other cases...

default:

return parser.query, fmt.Errorf("invalid query type")

}

And we can basically fill in the TODOs and profit! However, the diligent reader will see that the code for parsing the whole SELECT query can get messy really quickly, and we have many types of queries to parse. We’re gonna need some structure.

Finite-state Machines

FSMs are a super interesting topic, but we’re not here to get a CS degree. Let’s just focus on what we need.

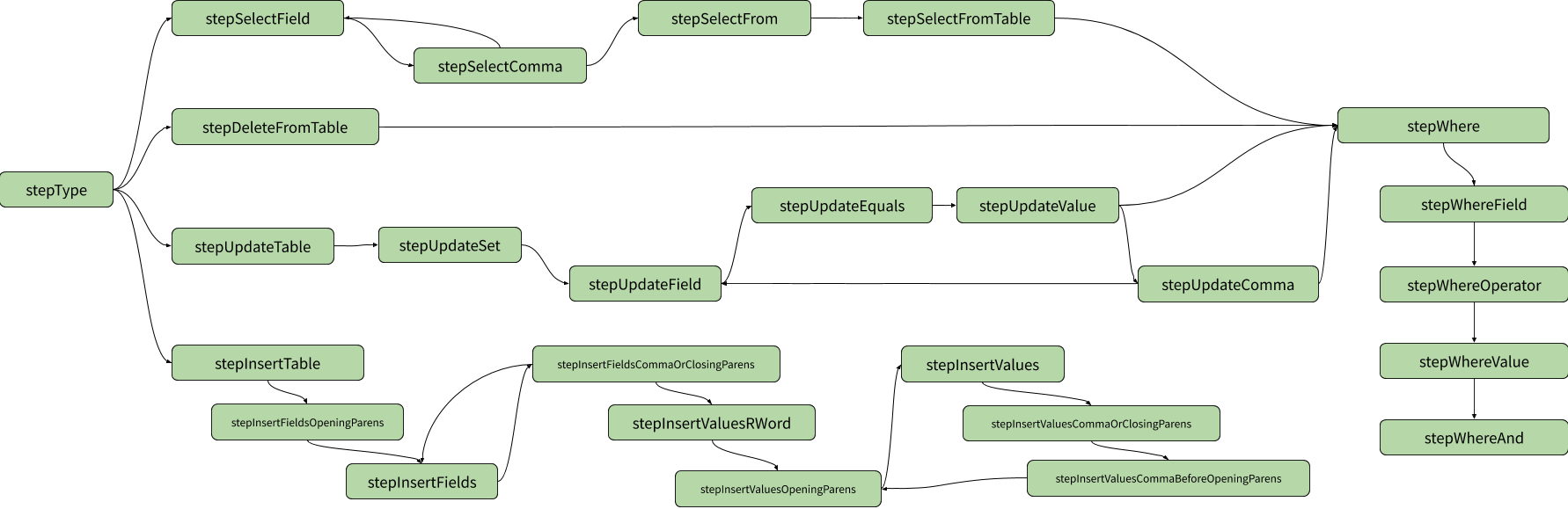

At any given point (instead of “point” let’s call it “node”) in our parsing journey, only a few tokens are valid, and upon finding these tokens we advance to new nodes where different tokens are valid, and so on until we finish parsing our query. We can visualise these node relationships as a directed graph:

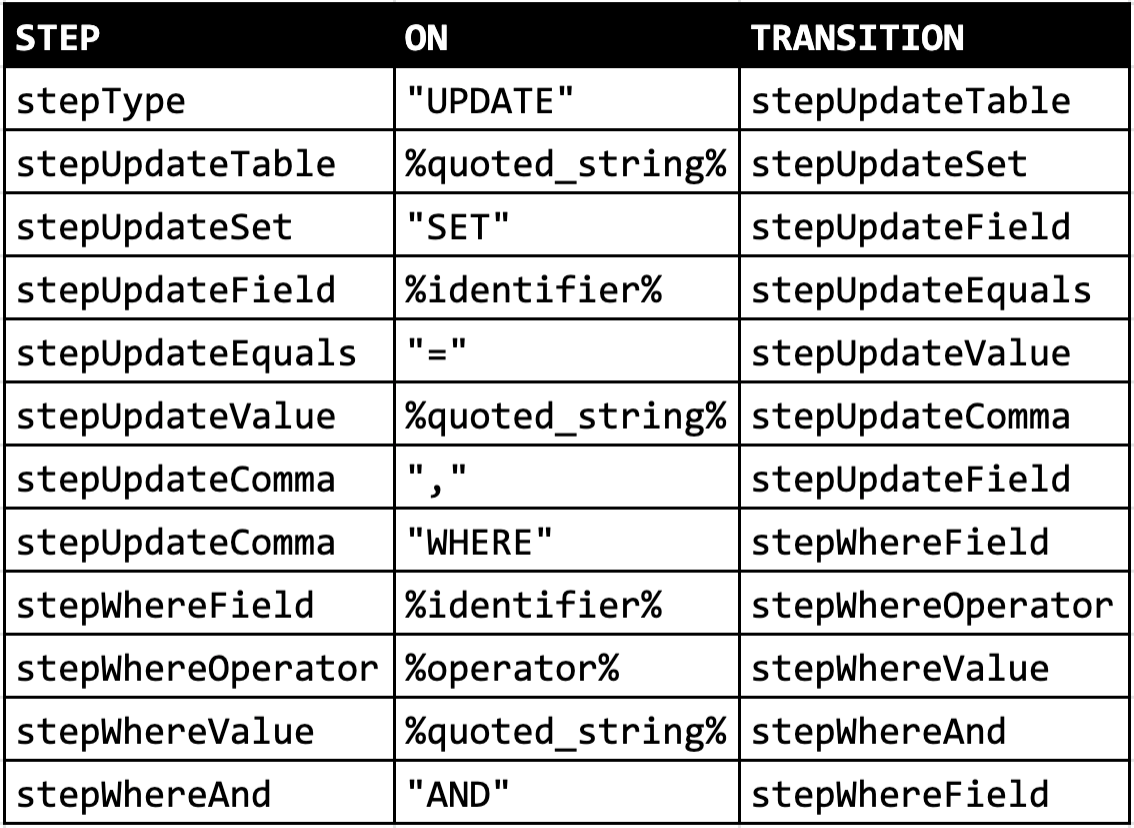

The node transitions can be defined with a simpler table, though:

We can directly translate this table to a really large switch statement. We’ll use that sneaky parser.step property we defined before:

func (p *parser) Parse() (query.Query, error) {

parser.step = stepType // initial step

for parser.i < len(parser.sql) {

nextToken := parser.peek()

switch parser.step {

case stepType:

switch nextToken {

case UPDATE:

parser.query.type = "UPDATE"

parser.step = stepUpdateTable

// TODO cases of other query types

}

case stepUpdateSet:

// ...

case stepUpdateField:

// ...

case stepUpdateComma:

// ...

}

parser.pop()

}

return parser.query, nil

}

And there we go! Note that some steps might conditionally cycle back to previous ones, like a comma on the SELECT field definition. This strategy scales well for basic parsers. As the grammar grows complex, though, the number of states will increase dramatically, so it can get tedious to write. I recommend testing as you code; more on that below.

Peek() implementation

Remember that we need to implement both peek() and pop(). Since they do almost the same, let’s use an auxiliary function to keep things DRY. Also, pop() should further advance the index to avoid peeking whitespace.

func (p *parser) peek() string {

peeked, _ := p.peekWithLength()

return peeked

}

func (p *parser) pop() string {

peeked, len := p.peekWithLength()

p.i += len

p.popWhitespace()

return peeked

}

func (p *parser) popWhitespace() {

for ; p.i < len(p.sql) && p.sql[p.i] == ' '; p.i++ {

}

}

Here’s a list of tokens that we might want to peek:

var reservedWords = []string{

"(", ")", ">=", "<=", "!=", ",", "=", ">", "<",

"SELECT", "INSERT INTO", "VALUES", "UPDATE",

"DELETE FROM", "WHERE", "FROM", "SET",

}

In addition to those, we might come across quoted strings or plain identifiers (e.g. field names). Here’s a hopefully complete peekWithLength() implementation:

func (p *parser) peekWithLength() (string, int) {

if p.i >= len(p.sql) {

return "", 0

}

for _, rWord := range reservedWords {

token := p.sql[p.i:min(len(p.sql), p.i+len(rWord))]

upToken := strings.ToUpper(token)

if upToken == rWord {

return upToken, len(upToken)

}

}

if p.sql[p.i] == '\'' { // Quoted string

return p.peekQuotedStringWithLength()

}

return p.peekIdentifierWithLength()

}

The remaining functions are trivial and left as an exercise to the reader. If you’re curious, the link at the TL;DR section contains the full source code implementation. I intentionally won’t link it again here to add a little indirection.

Final validation

The parser might find the end of the string before arriving at a complete query definition. It’s probably a good idea to implement a parser.validate() function that looks at the generated “query” struct, and returns an error if it’s incomplete or otherwise wrong.

Testing

Go’s table-driven testing pattern lends itself beautifully for our case:

type testCase struct {

Name string // description of the test

SQL string // input sql e.g. "SELECT a FROM 'b'"

Expected query.Query // expected resulting "query" struct

Err error // expected error result

}

Example tests:

ts := []testCase{

{

Name: "empty query fails",

SQL: "",

Expected: query.Query{},

Err: fmt.Errorf("query type cannot be empty"),

},

{

Name: "SELECT without FROM fails",

SQL: "SELECT",

Expected: query.Query{Type: query.Select},

Err: fmt.Errorf("table name cannot be empty"),

},

...

Test the test cases like this:

for _, tc := range ts {

t.Run(tc.Name, func(t *testing.T) {

actual, err := Parse(tc.SQL)

if tc.Err != nil && err == nil {

t.Errorf("Error should have been %v", tc.Err)

}

if tc.Err == nil && err != nil {

t.Errorf("Error should have been nil but was %v", err)

}

if tc.Err != nil && err != nil {

require.Equal(t, tc.Err, err, "Unexpected error")

}

if len(actual) > 0 {

require.Equal(t, tc.Expected, actual[0],

"Query didn't match expectation")

}

})

}

I’m using testify because it provides a diff output when the query structs don’t match.

Going deeper

This experiment is well-suited for:

- Learning LL(1) parser algorithms

- Custom parsing simple grammars with zero dependencies

However, this approach can get tedious and it’s somewhat limiting. Think about how to parse arbitrarily complex compound expressions (e.g. sqrt(a) = (1 * (2 + 3))).

For a more powerful parsing model, look into parser combinators. goyacc is a popular Go implementation.

I recommend this very interesting talk by Rob Pike on Lexical Scanning.

Recursive descent parsing is another parsing approach.

Why I wrote this

Recently, I’ve decided to centralise my data into a repository of CSVs. As a bonus, it’d give me a chance to learn React better by creating a UI for CRUDing the data. When I had to decide on an interface for communicating CRUD operations between frontend and backend, I felt SQL was a natural language for it (and I already know it well).

It seems that, although there are many libraries for reading CSV files with SQL, there aren’t many that support write operations (particularly DDL statements). A colleague recommended me to upload the files into an in-memory SQLite database, run the SQL and then export to CSV; a fine idea since performance wasn’t at all a concern for me. In the end, I thought to myself: didn’t you always want to write a SQL parser? How hard can it be?

Turns out writing a (basic) parser is very simple! But I bet it can appear daunting without a good tutorial that is as simple as can be.

I hope this can be that tutorial for you. KISS!